A few weeks ago I shared some data about the demographics and giving habits of the ultra wealthy on my blog Joyful Impact. It started some interesting conversations that I wanted to continue as we wrap up the end of the year.

Unless you’re wealthy yourself (meaning you have a net worth of $1 million or more), let alone ultra wealthy ($30 million or more), it might be hard to imagine what goes through the minds of the wealthy when they think about their giving.

Here’s what the data tells us about the ultra wealthy and their giving:

Globally there are just 264,000 people with a net worth of $50 million or more, according to Credit Suisse.

The majority of the ultra wealthy (roughly 140K) live in the US.

In New York City alone, 11,400 people have a net worth of more than $30 million, according to Wealth-X.

Even though we often think of “philanthropy” as the work of family foundations and other established institutional donors — individual giving by the ultra wealthy actually makes up almost 25 percent of global giving. Out of the $750 billion of global philanthropic giving in 2020, giving by ultra wealthy individuals accounted for $175.3 billion, or more than 23 percent.

This means that a tiny proportion of the world’s population — 1 in 30,000 people — are deciding where almost 1 in every 4 philanthropic dollars is going. The ultra wealthy thus have a tremendously disproportionate influence on which people, which organizations, and which solutions get resources.

Even though $30 million is a mind-boggling sum to many, in reality, many people with that net worth don’t have very much of that in liquid assets, so their annual giving capacity is typically in the tens of thousands of dollars, or occasionally hundreds of thousands, but very rarely millions.

It’s not until you hit the $100 million wealth threshold that you start seeing individual donors who are regularly giving $500,000 or more per year, and there are just 63,000 people at that level of wealth in the entire world.

The remaining 230,000 ultra wealthy individuals (those between $30 million and $100 million) can and do still give huge sums of money — but for the most part, they’re doing it without the help of philanthropic advisors.

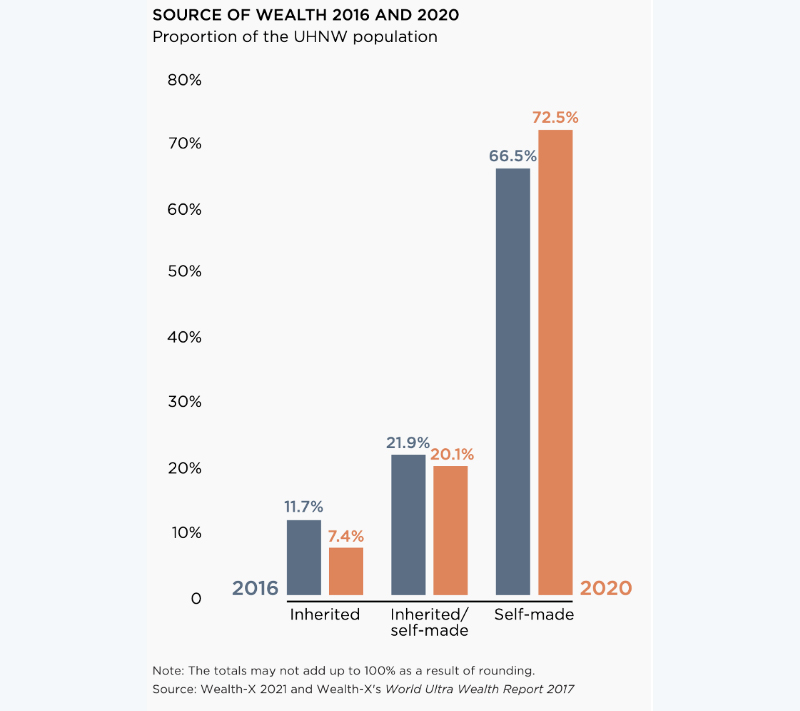

Lastly, contrary to popular belief, the data tells us that 72.5 percent of the ultra wealthy are completely self-made, while only 7.4 percent achieved ultra wealthy status by inheritance alone.

This suggests that the vast majority of the roughly 230,000 un-advised, ultra wealthy donors are entrepreneurs who were not born wealthy. They’re navigating an experience they were not trained for earlier in their life.

So what can philanthropic advisors do with this knowledge?

Here are my top takeaways.

Ultra wealthy individuals give in much the same way everyone else does

Even though they are dealing with orders of magnitude more money than most Americans, most of the ultra wealthy still give in the same way that we do: by writing checks out of their annual surplus. Whether they use a philanthropic tax vehicle, such as a donor advised fund, or give through other financial structures, many of them do a disproportionate share of their giving here at the end of the year when they see how much money they have to work with. Just like the average American, they respond to the appeals that are made to them, evaluate them as best they can with limited time, and write checks.

Ultra wealthy individuals are dissatisfied with the impact of their giving

From my own advising work, I know that a lot of UHNW donors feel stuck in their giving.

They get tied up in social obligations, giving in ways that feel petty. Someone gave to my thing, so I had to give to their thing…It will look bad if I don’t give to this group. And before they know it, they’re giving away hundreds of thousands of dollars a year, without seeing the impact or feeling much, if any, joy.

Many of them also feel like they don’t have enough money or time to get unstuck.

Because so many of the ultra wealthy come from working and middle class backgrounds, the value of a dollar is deeply ingrained in their psyche. The tradition they come from says you should steward your resources wisely, and that applies to their giving.

They feel like they don’t have the time to do the due diligence that they imagine it takes to find the most impactful organizations and maximize their impact, but they also don’t feel like it makes sense to spend the hundreds of thousands of dollars it might take to hire someone else to do that for them (a philanthropic advisor or a foundation staff).

The investment to create a giving strategy, hire people to implement it, and evaluate its impact (in essence, to engage in strategic philanthropy), would significantly decrease the amount of capital they could donate, and it would also take more time than they want to spend.

Achieving more impact requires a mindset shift that is especially hard for successful entrepreneurs

Fortunately, there are many ways donors can level up their impact and their fulfillment that don’t require them to “go pro” themselves or hire others to carry out their giving. I’ve outlined them in an article on my Joyful Impact blog: Gearing Up Your Giving: Strategic Philanthropy—And Six Alternatives.

However, again and again I’ve run into the same barrier that stops many donors from pursuing these alternatives: the story they tell themselves about their giving.

They feel the need to have a story about their giving that highlights their own agency. They want to be able to trace their dollars and their ideas to a unique and specific impact.

Again, this is a mindset that is ingrained in many of the ultra wealthy because of how they amassed their wealth. Rarely does anyone join the ranks of the ultra wealthy simply by backing other people’s ideas (check out Reiner Zeitelmann’s insightful research on the psychology of the ultra wealthy for more on this). Successful entrepreneurs very often have a track record of going against the grain — believing in themselves and their vision even when others do not. This pattern naturally leads you to attribute much of your success to your own hard work or ingenuity — and if you don’t expressly do it for yourself, our society has a tendency to make heroes out of entrepreneurs, giving front-page credit to the role of founders whenever an organization achieves success.

Let’s be clear: It’s totally reasonable to want to know that your money is really making a difference in the world. Nobody wants to feel like their money is disappearing into a bottomless hole of non-profit fundraising. And it’s also totally reasonable to feel that your values and your ideas matter, not just the scale of your financial assets. But when donors seek to meet these needs by casting themselves as the defining figure in their giving, it comes at a cost. When donors craft a narrative in which the meaning of their giving depends on attributing impact chiefly to their own unique ideas or their own specific dollars, they pay an ego tax — and they often don’t realize what they’re losing. That tax can come in the form of limited fulfillment and impact, or in the financial cost of having to hire people to help them sustain the story of their unique impact through a convoluted philanthropic strategy.

Advisors can help ultra wealthy individuals achieve more impact and fulfillment whether or not they are clients

The need for unique attribution is not only costly, it also rules out many opportunities for a more broadly shared contribution. The desire to attribute your gift to a specific outcome makes it hard to get behind the work other people are doing and accelerate their impact.

The strategy of working through others can be incredibly powerful and fulfilling. If more ultra wealthy individuals in that $30 million to $100 million range took this approach, the work of organizations like Black Voices for Black Justice could be dramatically accelerated. Or the Southern Reconstruction Fund. Or The 1954 Project. But many wealthy individuals don’t consider giving in these ways because they aren’t aware of these organizations or they haven’t challenged themselves to think about the story of their giving and its impact in new ways.

As philanthropic advisors, it’s important to remember that the pool of ultra wealthy individuals who have enough resources to hire us is much smaller than the total number of ultra wealthy individuals (perhaps only 50,000 out of almost 300,000) who have the level of resources that can make a game-changing difference for the social entrepreneurs who are out there tackling so many of the world’s toughest challenges. But even if we never meet with them or work with them, we can still be a positive resource for these donors.

- We can amplify the reach of social entrepreneurs who are having a tremendous impact.

- We can help shift the culture of philanthropy by lifting up the example of donors who lean into their role as accelerators and contributors, not just as entrepreneurial doers.

- We can be generous in making thoughtful recommendations to wealth advisors, estate attorneys, and all the various folks who reach out at this time of year asking for suggestions about where their clients can give.

- And we can model this shift from attribution to contribution in our own giving.

As we’re making our own end-of-the-year giving decisions, we should all consider what we lose when we center our need to trace the impact of our giving exclusively to our own direct donations. How much joy and impact can we all create by making space for the ideas and the leadership of others in the story of our giving?